page 28

Progressive Thinkers as of 12/1/2022

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Let us now consider the idea "intonation" which involves pitch:

in phonetics, the melodic pattern of an utterance. Intonation is primarily a matter of variation in the pitch level of the voice (see also tone), but in such languages as English, stress and rhythm are also involved. Intonation conveys differences of expressive meaning (e.g., surprise, anger, wariness).

In many languages, including English, intonation serves a grammatical function, distinguishing one type of phrase or sentence from another. Thus, "Your name is John," beginning with a medium pitch and ending with a lower one (falling intonation), is a simple assertion; "Your name is John?", with a rising intonation (high final pitch), indicates a question. ("intonation." Encyclopædia Britannicam, 2013.)

If we can distinguish tonal and non-tonal languages and that it is with the non-tonal languages from which the major ideas of Mathematics and the Sciences have arisen (by simply citing the country and language spoken by those who have produced so-called great ideas (Three examples will suffice for the moment:

- (1 person 3 laws); Johannes Kepler: German astronomer who discovered three major laws of planetary motion.

- (1 person 3 laws, 2 people for singular calculus idea from independent orientaions.); Sir Issac Newton: English physicist and mathematician, who was the culminating figure of the scientific revolution of the 17th century that discovered the three laws of motion. (He, along with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz of Germany, are credited with having independently come up with the Calculus.)

- (3 people, 1 idea); The French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur, the English surgeon Joseph Lister, and the German physician Robert Koch are given much of the credit for development and acceptance of the Germ theory.

In addition, let us note that very many Asian students seek an education at institutions whose dominant language is said to be non-tonal. Thus, does Tonal languages interfere with "Higher" cognitive functions along those areas we at present are viewing as major advances in intellectual development? If this is so, let us take this a step further and wonder if non-tonal languages interfere with a type of cognitive processes still waiting in the wings of the human brain but has difficulty of even getting its foot into the door of consciousness because of the emphasis being placed on such intellectual advancements, just as these advancements had to wait until it found a means to sneak its way into the suppressive tones of religion?

Let's now add a descriptive reference to the idea of Chant Intonation... where "tonation" and "intonation" appear to cross paths and are used inter-changeably (that is if we are to view "pitch" as a qualification for non-tonal languages):

Chant intonation

The chanting of the Rigveda and Yajurveda shows, with some exceptions, a direct correlation with the grammar of the Vedic language. As in ancient Greek, the original Vedic language was accented, with the location of the accent often having a bearing on the meaning of the word. In the development of the Vedic language to Classical Sanskrit, the original accent was replaced by an automatic stress accent, whose location was determined by the length of the word and had no bearing on its meaning. It was thus imperative that the location of the original accent be inviolate if the Vedic texts were to be preserved accurately.

The original Vedic accent occurs as a three-syllable pattern:

- The central syllable, called udatta, receives the main accent;

- The preceding syllable, anudatta, is a kind of preparation for the accent;

- The following syllable, svarita, is a kind of return from accentuation to accentlessness.

There is some difference of opinion among scholars as to the nature of the original Vedic accent; some have suggested that it was based on:

- Pitch,

- others on Stress;

- and one theory proposes that it referred to the relative height of the tongue.

In the most common style of Rigvedic and Yajurvedic chanting found today, that of the Tamil Aiyar Brahmans, it is clear that the accent is differentiated in terms of pitch. This chanting is based on three tones:

- The udatta and the nonaccented syllables (called prachaya) are recited at a middle tone,

- The preceding anudatta syllable at a low tone,

- and the following svarita syllable either at the high tone (when the syllable is short) or as a combination of middle tone and high tone.

The intonation of these tones is not precise, but the lower interval is very often about a whole tone, while the upper interval tends to be slightly smaller than a whole tone but slightly larger than a semitone. In this style of chanting the duration of the tones is also relative to the length of the syllables, the short syllables generally being half the duration of the long.

The more musical chanting of the Samaveda employs:

- Five tones,

- Six tones,

- or Seven tones and is said to be the source of the later secular and classical music.

From some of the phonetic texts that follow the Vedic literature, it is apparent that certain elements of musical theory were known in Vedic circles, and there are references to three octave registers (sthana), each containing seven notes (yama).

An auxiliary text of the Samaveda, the Naradishiksha, correlates the Vedic tones with the accents described above, suggesting that the Samavedic tones possibly derived from the accents. The Samavedic hymns as chanted by the Tamil Aiyar Brahmans are based on a mode similar to the D mode (D-d on the white notes of the piano; i.e., the ecclesiastical Dorian mode).

- But the hymns seem to use three different-sized intervals, in contrast to the two sizes found in the Western church modes.

- They are approximately 1) a whole tone, 2) a semitone, and 3) an intermediate tone.

Once again, the intervals are not consistent and vary both from one chanter to another and within the framework of a single chant. The chants are entirely unaccompanied by instruments, and this may account for some of the extreme variation of intonation.

The changes brought by the 20th century weakened the traditional prominent position of the Vedic chant. The Atharvaveda is seldom heard in India now. Samavedic chant, associated primarily with the large public sacrifices, also appears to be dying out. Even the Rigveda and Yajurveda are virtually extinct in some places, and South India is now the main stronghold of Vedic chant.

I placed a "squared" item in the preceding to make a comment concerning the presence of having a 3 and 2-sizes difference. The mention that the "Western" church used "two" and not "three" sizes is an important distinction when contrasting cognitive development, when the "three" in so very many cases expresses a maturational development exceeding a "two" pattern. I am of course associating the "two" with tonal languages and a preference for duality, where the "three" is being associated with non-tonal languages and triplicity.

Not only do we need to tentatively accept the idea that human cognition follows a linear path of progression one might reference in term of a basic number line such as 1- 2- 3, but refuse to expect the number line not to have digressions into fractions, fitful stops and starts, reversals, as well as leaps from one point to the next with or without any clear or apparent reason. Since Evolution has shown us from the historical record that a analogically appropriated developmental number line need not be nice, neat or even necessary, let us proceed along the "number line progression" view with great latitude and deference to expressions of a sequential line quite different than a stoic arithmetical progression used by those whose personal level of insecurity prefers a stoic model of expression.

So, on the one hand we have the Chinese who express a cognitive orientation to nature with an adopted two-patterned philosophy called the yin/yang (model). Along with this model is the use of artistically inclined expressions called calligraphy. Somewhere along the line in history Chinese numerology is developed to attest to a changing cognitive activity. Yet, no advanced mathematics is produced. Perhaps it is due to China's relative isolation and little need for a lingua franca among different traders, because most of China's trade was done internally, though variations of the Chinese dialect prevailed. Still, it differed from the experiences of the Indo-European trade market where languages... although perhaps from a supposed Indo-European "Mother tongue" or a labeled proto- Indo-European language; were multiple. And the same goes for warring factions. In most cases one might argue, China fought internal wars, while Europeans fought those external to a respective country, people and culture. Again we see what we can generally describe as a singular instance compared to one of multiplicity. While there are multiple Chinese factions to be named, they are all Chinese. And while one might likewise argue that all groups in Europe were European; there were sometimes vast differences in fighting techniques and lifestyles. Yet, the Chinese in many respects were far ahead of other peoples... particularly the Europeans.

However, when making a comparison between the Chinese as a "single" people where fighting and commerce took place within a place called "China", it is easy to overlook the fact that the size of China is almost the size of all Europe, and that the people whom the rest of the world designate as being Chinese, had language differences similar to those encountered among different European peoples:

"Chinese": also called Sinitic languages, Chinese Han, (is the) principal language group of eastern Asia, belonging to the Sino-Tibetan language family. Chinese exists in a number of varieties that are popularly called dialects but that are usually classified as separate languages by scholars. More people speak a variety of Chinese as a native language than any other language in the world, and Modern Standard Chinese is one of the six official languages of the United Nations.

The spoken varieties of Chinese are mutually unintelligible to their respective speakers. They differ from each other to about the same extent as the modern Romance languages. Most of the differences among them occur in pronunciation and vocabulary; there are few grammatical differences. These languages include Mandarin in the northern, central, and western parts of China; Wu; Northern and Southern Min; Gan (Kan); Hakka (Kejia); and Xiang; and Cantonese (Yue) in the southeastern part of the country.

All the Chinese languages share a common literary language (wenyan), written in characters and based on a common body of literature. This literary language has no single standard of pronunciation; a speaker of a language reads texts according to the rules of pronunciation of his own language. Before 1917 the wenyan was used for almost all writing; since that date it has become increasingly acceptable to write in the vernacular style (baihua) instead, and the old literary language is dying out in the daily life of modern China. (Its use continues in certain literary and scholarly circles.)

In the early 1900s a program for the unification of the national language, which is based on Mandarin, was launched; this resulted in Modern Standard Chinese. In 1956 a new system of romanization called Pinyin, based on the pronunciation of the characters in the Beijing dialect, was adopted as an educational instrument to help in the spread of the modern standard language. Modified in 1958, the system was formally prescribed (1979) for use in all diplomatic documents and foreign-language publications in English-speaking countries.

Some scholars divide the history of the Chinese languages into Proto-Sinitic (Proto-Chinese; until 500 BC), Archaic (Old) Chinese (8th to 3rd century BC), Ancient (Middle) Chinese (through AD 907), and Modern Chinese (from c. the 10th century to modern times). The Proto-Sinitic period is the period of the most ancient inscriptions and poetry; most loanwords in Chinese were borrowed after that period. The works of Confucius and Mencius mark the beginning of the Archaic Chinese period. Modern knowledge of the sounds of Chinese during the Ancient Chinese period is derived from a pronouncing dictionary of the language of the Ancient period published in AD 601 by the scholar Lu Fayan and also from the works of the scholar-official Sima Guang, published in the 11th century. ("Chinese languages." Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013.)

The Tocharian languages, now extinct, were spoken in the Tarim Basin (in present-day northwestern China) during the 1st millennium AD. Two distinct languages are known, labeled A (East Tocharian, or Turfanian) and B (West Tocharian, or Kuchean). One group of travel permits for caravans can be dated to the early 7th century, and it appears that other texts date from the same or from neighbouring centuries. These languages became known to scholars only in the first decade of the 20th century; they have been less important for Indo-European studies than has Hittite, partly because their testimony about the Indo-European parent language is obscured by 2,000 more years of change and partly because Tocharian testimony fits fairly well with that of the previously known non-Anatolian languages. ("Indo-European languages." Encycloæædia Britannica, 2013.)

The reason for including the topic of Chinese languages is to point out that the diversity of European languages may not have been as large a factor in b ringing about the ideological differences which reference a vast difference in the cognitive additives of the Chinese. In other, more simpler terms: When trying to figure out what factors may have kept the Chinese from developing the philosophy, math, medicine and other sciences (including the use of gunpowder as a propellant in war armaments) when they were obviously more advanced in other regards than the Europeans; the presence of differences in languages may not have been as important as one might initially assume. Then again, since Chinese is a tonal language and Europeans, for the most part have non-tonal languages, one might consider that it is the tonal languages which have interfered with the development of higher cognitive functions called Science and Mathematics, if not Philosophy as well, at least in some regard.

If we agree that a generalized number sequence can be used to describe cognitive activity, we must ask why the Chinese didn't continue their obvious cognitive superiority... unless we are to assume it is like the requirement of other life forms which need to mature quickly with respect to the prevailing environment... such as can be described and viewed with respect to jungle primates. If this is not the case, then again, let us ask why the Chinese did not develop into a "three" orientation as it did with the yin/yang "two" orientation? Whereas we can see the beginnings of a three-patterned mindset with the advent of the I-Ching triads, and not an inroad to more complex number usage such as Mathematics, let us note that the Triads in the I-Ching are actually embellished Biads. One need only look at the triads to note that there is no 3-line configuration places along single and double lines. What we see is a repetition of the single or double-line models of expression, which reflect the former identification with male and female sexual body parts. Namely, the singe line represents the male penis and the double line the female vagina. Hence, while there was a developmental attempt to express a cognitively-aligned "three-patterned" perspective, what we have is a lingered attachment to a former two-patterned male/female form, much in the manner as one might describe a mamma's boy or daddy's little girl psychology. It is an expressed lingering in a childhood frame of mind one might suggest as being seen in some Chinese movies where older children are not only treated like young kids, but they whine a lot as if it is expected of them to remain attached to their parents in a sub-servient role of immaturity... and criticisms against such "baby talk" amongst older kids portrayed in movies creates a situation in which it is thought that if an actor or actress acts very serious and stoic, they exhibit some ultimate model of maturity, intelligence and wisdom.

When the Europeans had developed to the point where a maturity of mind would allow for them to experience a pattern-of-two orientation to nature long after the Chinese yin/yang cognitive model, there was no comparable artistic flair to be developed. Instead, there was a gradual upsurge in the use of numbers, though the ancient Egyptians did use pictographs for a time to illustrate different values of enumeration. However, the use of "pictures" must have been thought to be too cumbersome since they became replaced with variations of (at first) simple lines and circles like one might see as notches on a bone described as a tally stick; that were later replaced with combinations of individual lines which took on a semi-calligraphic sense of expression by intersections of lines being used which conformed to an interpretation the image of a wedged instrument would make on a soft piece of clay to produce what we of today call cuneiform writing. While my intent is not to give a full historical count of the development of writing, the point I want to stress is that Europeans did not also resort to an elaborate form of artistic writing like Chinese calligraphy, which caught on with the Chinese because it gained a wide-spread appeal due to the type of sensitivity and sensibility which the imaginative Chinese mind had available to it. Europeans were, on the whole, and in a collective sense, less artistically inclined to adopt a singular model of expression as a means of communicating multiple perceptions and feelings as well as thoughts evoked by such impressions.

For its two-patterned cognitive journey, Europeans eventually adopted Mathematics, through a travail of navigating a course through a use of numbers used by part-time number users calling themselves philosophers. Individuals for the most part who were using their personal inclinations to offer numbers as a means of offering proof for some speculation for which the philosophies of old did not require any substantial proofing system for establishing a believed-in truth. Those who began to work with numbers on a full-time basis and had developed a certain rigor of not wanting to think in speculative philosophical terms alone, be it due to a further change in human cognition; needed to start their own club of investigators into the realities of Nature, whereby they were free to develop their own proofs and pursue depths of observations from vantage points that typical philosophers do not discipline themselves towards.

Let me now provide some Britannica excerpts which are relative to the present model of discussion, with the note that in the Chinese Calligraphy comments, I interpret the word "stroke" as another way of saying "line", albeit with an artistic flair:

From prehistory through Classical Greece

The ability to count dates back to prehistoric times. This is evident from archaeological artifacts, such as a 10,000-year-old bone from the Congo region of Africa with tally marks scratched upon it—signs of an unknown ancestor counting something. Very near the dawn of civilization, people had grasped the idea of "multiplicity" and thereby had taken the first steps toward a study of numbers.

It is certain that an understanding of numbers existed in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and India, for tablets, papyri, and temple carvings from these early cultures have survived. A Babylonian tablet known as Plimpton 322 (c. 1700 BC) is a case in point. In modern notation, it displays number triples x, y, and z with the property that x2 + y2 = z2. One such triple is 2,291, 2,700, and 3,541, where 2,2912 + 2,7002 = 3,5412. This certainly reveals a degree of number theoretic sophistication in ancient Babylon.

Despite such isolated results, a general theory of numbers was nonexistent. For this—as with so much of theoretical mathematics—one must look to the Classical Greeks, whose ground-breaking achievements displayed an odd fusion of the mystical tendencies of the Pythagoreans and the severe logic of Euclid's Elements (c. 300 BC).

Pythagoras

According to tradition, Pythagoras (c. 580–500 BC) worked in southern Italy amid devoted followers. His philosophy enshrined number as the unifying concept necessary for understanding everything from planetary motion to musical harmony. Given this viewpoint, it is not surprising that the Pythagoreans attributed quasi-rational properties to certain numbers.

For instance, they attached significance to perfect numbers—i.e., those that equal the sum of their proper divisors. Examples are 6 (whose proper divisors 1, 2, and 3 sum to 6) and 28 (1 + 2 + 4 + 7 + 14). The Greek philosopher Nicomachus of Gerasa (flourished c. AD 100), writing centuries after Pythagoras but clearly in his philosophical debt, stated that perfect numbers represented "virtues, wealth, moderation, propriety, and beauty." (Some modern writers label such nonsense numerical theology.)

In a similar vein, the Greeks called a pair of integers amicable ("friendly") if each was the sum of the proper divisors of the other. They knew only a single amicable pair: 220 and 284. One can easily check that the sum of the proper divisors of 284 is 1 + 2 + 4 + 71 + 142 = 220 and the sum of the proper divisors of 220 is 1 + 2 + 4 + 5 + 10 + 11 + 20 + 22 + 44 + 55 + 110 = 284. For those prone to number mysticism, such a phenomenon must have seemed like magic.

Euclid

By contrast, Euclid presented number theory without the flourishes. He began Book VII of his Elements by defining a number as "a multitude composed of units." The plural here excluded 1; for Euclid, 2 was the smallest "number." He later defined a prime as a number "measured by a unit alone" (i.e., whose only proper divisor is 1), a composite as a number that is not prime, and a perfect number as one that equals the sum of its "parts" (i.e., its proper divisors).

From there, Euclid proved a sequence of theorems that marks the beginning of number theory as a mathematical (as opposed to a numerological) enterprise.

Professor of Mathematics, Muhlenberg College, Allentown, Pennsylvania. Author of Euler the Master of Us All and others. ("number theory." Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013.)

Chinese Calligraphy is the stylized, artistic writing of Chinese characters, the written form of Chinese that unites the languages (many mutually unintelligible) spoken in China. Because calligraphy is considered supreme among the visual arts in China, it sets the standard by which Chinese painting is judged. Indeed, the two arts are closely related.

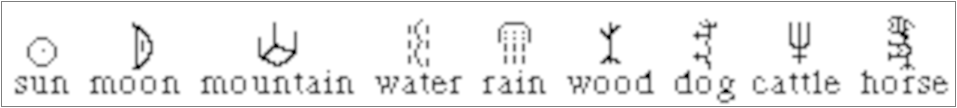

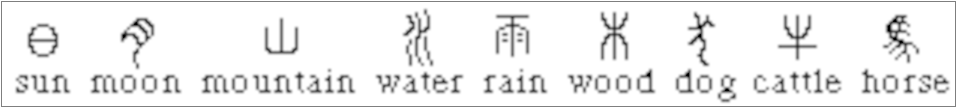

The early Chinese written words were simplified pictorial images, indicating meaning through suggestion or imagination. These simple images were flexible in composition, capable of developing with changing conditions by means of slight variations.

The earliest known Chinese logographs are engraved on the shoulder bones of large animals and on tortoise shells. For this reason the script found on these objects is commonly called jiaguwen, or shell-and-bone script. It seems likely that each of the ideographs was carefully composed before it was engraved. Although the figures are not entirely uniform in size, they do not vary greatly in size. They must have evolved from rough and careless scratches in the still more distant past. Since the literal content of most jiaguwen is related to ancient religious, mythical prognostication or to rituals, jiaguwen is also known as oracle bone script. Archaeologists and paleographers have demonstrated that this early script was widely used in the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE). Nevertheless, the 1992 discovery of a similar inscription on a potsherd at Dinggongcun in Shandong province demonstrates that the use of a mature script can be dated to the late Neolithic Longshan culture (c. 2600–2000 BCE).

It was said that Cangjie, the legendary inventor of Chinese writing, got his ideas from observing animals' footprints and birds' claw marks on the sand as well as other natural phenomena. He then started to work out simple images from what he conceived as representing different objects such as those that are given below:

First Stage: Surely, the first images that the inventor drew of these few objects could not have been quite so stylized but must have undergone some modifications) to reach the above stage. Each image is composed of a minimum number of lines and yet is easily recognizable. Nouns no doubt came first. Later, new ideographs had to be invented to record actions, feelings, and differences in size, colour, taste, and so forth. Something was added to the already existing ideograph to give it a new meaning. The ideograph for (one) 'deer,' for instance, is not a realistic image but a much simplified structure of lines suggesting a deer by its horns, big eye, and small body, which distinguish it from other animals. When two such simple images are put side by side, the meaning is 'pretty,' 'prettiness,' 'beautiful,' 'beauty,' etc., which is obvious if one has seen two such elegant creatures walking together. However, if a third image is added above the other two, as , it means 'rough,' 'coarse,' and even 'haughty.' This interesting point is the change in meaning through the arrangement of the images. If the three creatures were not standing in an orderly manner, they could become rough and aggressive to anyone approaching them. From the aesthetic point of view, three such images could not be arranged side by side within an imaginary square without cramping one another, and in the end none would look like a deer at all.

Jiaguwen was followed by a form of writing found on bronze vessels associated with ancestor worship and thus known as jinwen ("metal script"). Wine and raw or cooked food were placed in specially designed cast bronze vessels and offered to the ancestors in special ceremonies. The inscriptions, which might range from a few words to several hundred, were incised on the insides of the vessels. The words could not be roughly formed or even just simple images; they had to be well worked out to go with the decorative ornaments outside the bronzes, and in some instances they almost became the chief decorative design themselves. Although they preserved the general structure of the bone-and-shell script, they were considerably elaborated and beautified. Each bronze or set of them may bear a different type of inscription, not only in the wording but also in the manner of writing. Hundreds were created by different artists.

Second Stage: The bronze script—which is also called guwen ("ancient script"), or dazhuan ("large seal") script—represents the second stage of development in Chinese calligraphy.

When China was united for the first time, in the 3rd century BCE, the bronze script was unified and regularity enforced. Shihuangdi, the first emperor of Qin, gave the task of working out the new script to his prime minister, Li Si, and permitted only the new style to be used. The following words can be compared with similar words in bone-and-shell script:

This third stage in the development of Chinese calligraphy was known as xiaozhuan ("small seal") style. Small-seal script is characterized by lines of even thickness and many curves and circles. Each word tends to fill up an imaginary square, and a passage written in small-seal style has the appearance of a series of equal squares neatly arranged in columns and rows, each of them balanced and well-spaced. This uniform script had been established chiefly to meet the growing demands for record keeping.

Fourth Stage: Unfortunately, the small-seal style could not be written speedily and therefore was not entirely suitable, giving rise to the fourth s stage, lishu, or official style. (The Chinese word li here means "a petty official" or "a clerk"; lishu is a style specially devised for the use of clerks.) Careful examination of lishu reveals no circles and very few curved lines. Squares and short straight lines, vertical and horizontal, predominate. Because of the speed needed for writing, the brush in the hand tends to move up and down, and an even thickness of line cannot be easily achieved.

Lishu is thought to have been invented by Cheng Miao (240–207 BCE), who had offended Shihuangdi and was serving a 10-year sentence in prison. He spent his time in prison working out this new development, which opened up seemingly endless possibilities for later calligraphers. Freed by lishu from earlier constraints, they evolved new variations in the shape of strokes and in character structure. The words in lishu style tend to be square or rectangular with a greater width than height. While stroke thickness may vary, the shapes remain rigid; for instance, the vertical lines had to be shorter and the horizontal ones longer.

Fifth stage: As this curtailed the freedom of hand to express individual artistic taste, a fifth stage developed—zhenshu (kaishu), or regular script. No individual is credited with inventing this style, which was probably created during the period of the Three Kingdoms and Xi Jin (220–317). The Chinese write in regular script today; in fact, what is known as modern Chinese writing is almost 2,000 years old, and the written words of China have not changed since the first century of the Common Era.

"Regular script" means "the proper script type of Chinese writing" used by all Chinese for government documents, printed books, and public and private dealings in important matters ever since its establishment. Since the Tang period (618–907 CE), each candidate taking the civil service examination was required to be able to write a good hand in regular style. This imperial decree deeply influenced all Chinese who wanted to become scholars and enter the civil service. Although the examination was abolished in 1905, most Chinese up to the present day try to acquire a hand in regular style.

In zhenshu each stroke, each square or angle, and even each dot can be shaped according to the will and taste of the calligrapher. Indeed, a word written in regular style presents an almost infinite variety of problems of structure and composition, and, when executed, the beauty of its abstract design can draw the mind away from the literal meaning of the word itself.

The greatest exponents of Chinese calligraphy were Wang Xizhi and his son Wang Xianzhi in the 4th century. Few of their original works have survived, but a number of their writings were engraved on stone tablets and woodblocks, and rubbings were made from them. Many great calligraphers imitated their styles, but none ever surpassed them for artistic transformation.

Wang Xizhi not only provided the greatest example in the regular script, but he also relaxed the tension somewhat in the arrangement of the strokes in the regular style by giving easy movement to the brush to trail from one word to another. This is called xingshu, or running script. This, in turn, led to the creation of caoshu, or grass script, which takes its name from its resemblance to windblown grass—disorderly yet orderly. The English term cursive writing does not describe grass script, for a standard cursive hand can be deciphered without much difficulty, but grass style greatly simplifies the regular style and can be deciphered only by seasoned calligraphers. It is less a style for general use than for that of the calligrapher who wishes to produce a work of abstract art.

Technically speaking, there is no mystery in Chinese calligraphy. The tools for Chinese calligraphy are few—an ink stick, an ink stone, a brush, and paper (some prefer silk). The calligrapher, using a combination of technical skill and imagination, must provide interesting shapes to the strokes and must compose beautiful structures from them without any retouching or shading and, most important of all, with well-balanced spaces between the strokes. This balance needs years of practice and training.

The fundamental inspiration of Chinese calligraphy, as of all arts in China, is nature. In regular script each stroke, even each dot, suggests the form of a natural object. As every twig of a living tree is alive, so every tiny stroke of a piece of fine calligraphy has the energy of a living thing. Printing does not admit the slightest variation in the shapes and structures, but strict regularity is not tolerated by Chinese calligraphers, especially those who are masters of the caoshu. A finished piece of fine calligraphy is not a symmetrical arrangement of conventional shapes but, rather, something like the coordinated movements of a skillfully composed dance—impulse, momentum, momentary poise, and the interplay of active forces combining to form a balanced whole.

Painter, Professor of Chinese, Columbia University, 1968–71. Author of Chinese Calligraphy and others. ("Chinese calligraphy." Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013.

The so-called "stroke" used in Chinese calligraphy with a counter-part whenever a brush is used such as in painting, can be viewed in term of being representative of a line, dash or event called a segment. The need for recognizing such correspondences is so that a basic theme of human cognitive activity can be recognized in multiple subjects and activities as having a congruent similarity. The "stroke" can be viewed as having a cognitive similarity to the "line" used in an format of counting referenced as a tally, whether kept on a bone, clay tablet, rope, shell, or otherwise.

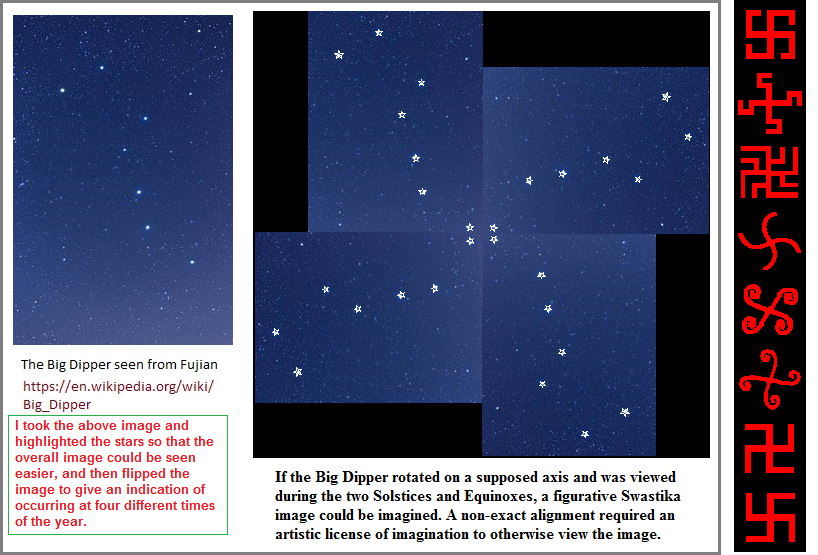

However, I want to bring to the fore the idea that not all tally mediums where mobile or small. Nor, let me suggest, were they affixed on Earth. What I am describing is that while we can find tally references to the motions of time such as the passage of the moon, humans could well have created forms of tallys that displayed positions of stars like the Big Dipper. I can not say if all groupings or individual stars were tallied in such a way, but the symbol we call the Swastika may well be a means by which the Big Dipper's position was tallied during the two solstices and two equinoxes. And yes, I came upon this idea this day (11/25/2022 at around 9:30 AM) while discussing various topics with a Friend called Richard Williams, who has a vast array of information on multiple topics because of his voracious reading habit. I actually blurted out the idea in response to a comment of his regarding some ancient tally bone used as a chronicling device of some natural event. Like a poem which "pops" into mind, the image was revealed in so many words. It is interesting enough of an idea to provide a record of it.

Swastika: equilateral cross with arms bent at right angles, all in the same rotary direction, usually clockwise. The swastika as a symbol of prosperity and good fortune is widely distributed throughout the ancient and modern world. The word is derived from the Sanskrit svastika, meaning "conducive to well-being." It was a favourite symbol on ancient Mesopotamian coinage. In Scandinavia the left-hand swastika was the sign for the god Thor's hammer. The swastika also appeared in early Christian and Byzantine art (where it became known as the gammadion cross, or crux gammata, because it could be constructed from four Greek gammas [ Γ ] attached to a common base), and it occurred in South and Central America (among the Maya) and in North America (principally among the Navajo).

In India the swastika continues to be the most widely used auspicious symbol of Hindus, Jainas, and Buddhists. Among the Jainas it is the emblem of their seventh Tirthankara (saint) and is also said to remind the worshiper by its four arms of the four possible places of rebirth—in the animal or plant world, in hell, on Earth, or in the spirit world.

The Hindus (and also Jainas) use the swastika to mark the opening pages of their account books, thresholds, doors, and offerings. A clear distinction is made between the right-hand swastika, which moves in a clockwise direction, and the left-hand swastika (more correctly called the sauvastika), which moves in a counterclockwise direction. The right-hand swastika is considered a solar symbol and imitates in the rotation of its arms the course taken daily by the Sun, which in the Northern Hemisphere appears to pass from east, then south, to west. The left-hand swastika more often stands for night, the terrifying goddess Ka-li-, and magical practices.

In the Buddhist tradition the swastika symbolizes the feet, or the footprints, of the Buddha. It is often placed at the beginning and end of inscriptions, and modern Tibetan Buddhists use it as a clothing decoration. With the spread of Buddhism, the swastika passed into the iconography of China and Japan, where it has been used to denote plurality, abundance, prosperity, and long life.

In Nazi Germany the swastika (German: Hakenkreuz), with its oblique arms turned clockwise, became the national symbol. In 1910 a poet and nationalist ideologist Guido von List had suggested the swastika as a symbol for all anti-Semitic organizations; and when the National Socialist Party was formed in 1919–20, it adopted it. On Sept. 15, 1935, the black swastika on a white circle with a red background became the national flag of Germany. This use of the swastika ended in World War II with the German surrender in May 1945, though the swastika is still favoured by neo-Nazi groups.

"swastika." Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013.

Later examinations of the Swastika took on the interpretations of those who chose to use it and were unable to intellectually discern the origin of the Swastika which predated any symbol they might use to "prove" its value and representation of a given idea far removed in time and place from the original setting who used the swastika illustration as a type of tally stick which marked the motion of human cognitive activity being attached to the big dipper like some light source for which the human mind acted as a moth being attracted to it.

Date of (series) Origination: Saturday, 14th March 2020... 6:11 AM

Date of Initial Posting (this page): 9th January 2023... 12:30 AM AST (Arizona Standard Time); Marana, AZ.