(and Astronomy)

Page 2

~ The Study of Threes ~

http://threesology.org

| Threes in Physics page 1 | Threes in Physics page 2 | 3 (mem)brane Universe page 1 | 3 (mem)brane Universe page 2 | 3 (mem)brane Universe page 3 |

Visitors as of 8/29/2020

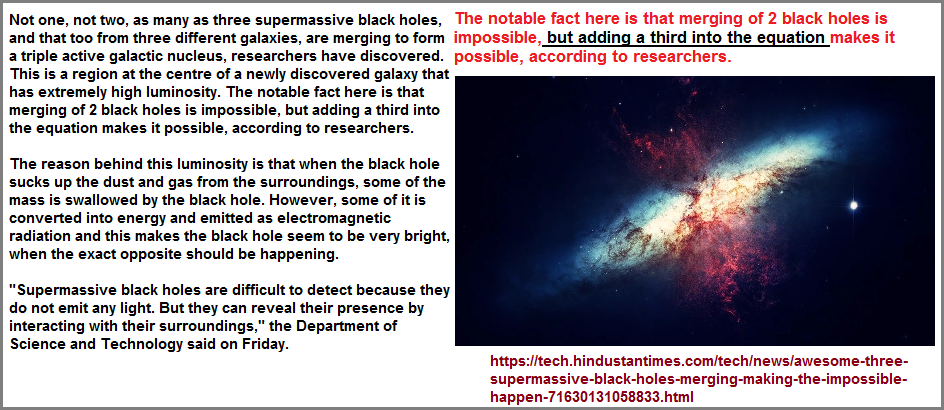

Awesome! THREE supermassive black holes merging; making the impossible happen by Hi Tech, 28 Aug 2021, 11:45 AM IST

Experiment Confirms Third Type of Subatomic Particles Called Anyons by Anton Petrov

Many people are either consciously or unconsciously aware of the recurring "threes" presence in physics. Whereby if you want to promote an alternative theory, it is safe for you to present one with a threes theme. Like many a writer of fairytales (no I am not saying the idea of Anyons is a Fairytale,) it is a valuable tool to use a threes theme in concocting an entirely new tale or revising an old one, such as in the case for creating a screen or stage play. For those readers who are not familiar with the "threes" theme in fairytales, or need a moment's refresher:

- 3 bears (Goldilocks and the 3 bears. By including Goldilocks we have a 3 to 1 ratio.)

- 3 pigs (By including the wolf who huffs, puffs and blows at their dwellings, we have another 3 to 1 ratio.)

- Old King Cole and his fiddlers 3.

- Three Blind mice. (More of a short poem than a story.)

- Three Billy Goats Gruff.

- Three Magic Beans for the tale "Jack and the Beanstalk", though different variations of the story provide different quantities of beans... perhaps helping to describe its antiquity and cultural origination.

- Why fairytales often feature a triple

- Significance of the number 3 in fairy tales

- Two Plus One is Greater than Three: The Presence of the Number 3 in Fairytales and Folklore

- Threes Poster column 4

- The usage of "seven" in Snow White and the seven dwarfs bespeaks of an ancient origin when the number "7" played a dominant role in some cultural venues, linking it to the notions of the seven stars of the Big Dipper (From which the Swastika originates by aligning the Dipper with the two Solstices and two Equinoxes), the seven stars (sisters) of the Pleiades, and the ideas concerning the quantity of planets thought to exist at one time... as well as the quantity of rings surrounding Saturn (The seven main rings are labeled in the order in which they were discovered. From the planet outward, they are D, C, B, A, F, G and E. The D ring is very faint and closest to Saturn. The main rings are A, B and C.)... from which the custom of wearing a wedding ring is said to have originated.

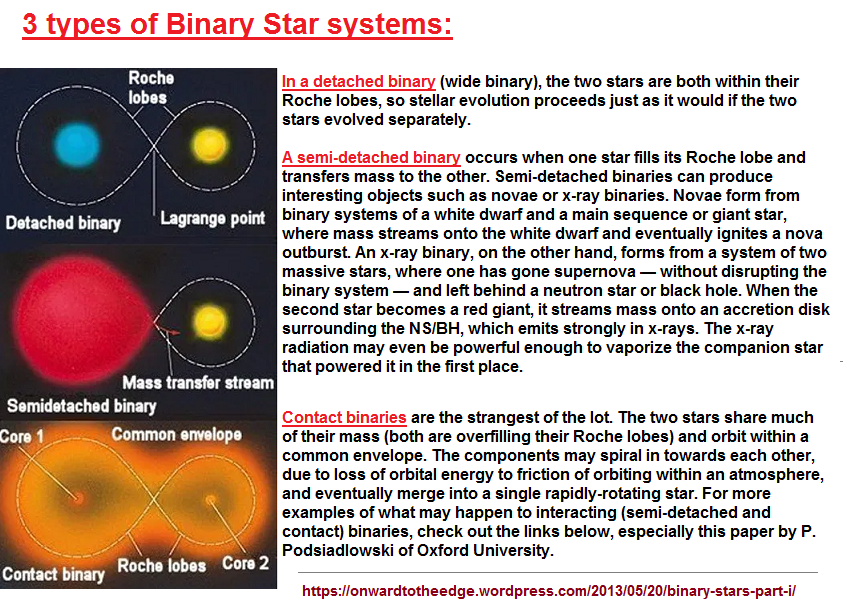

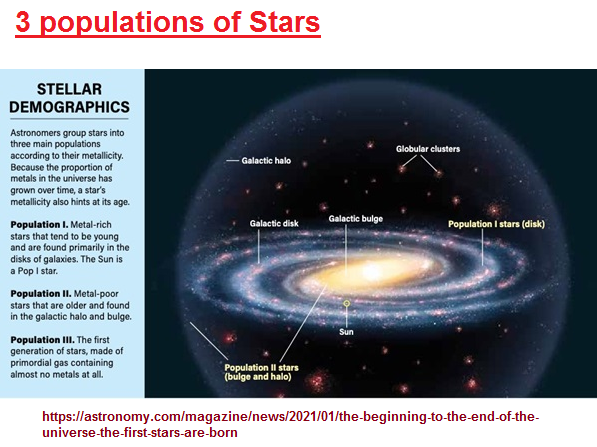

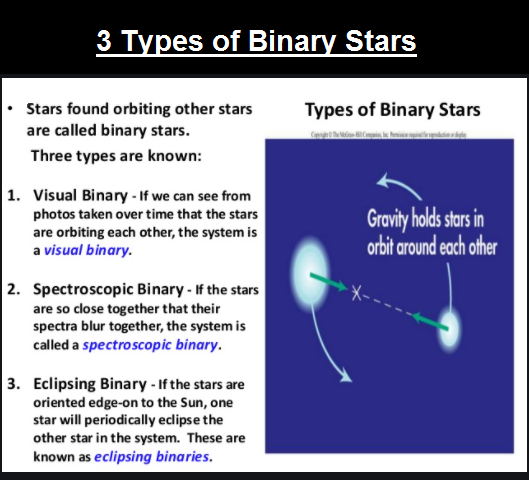

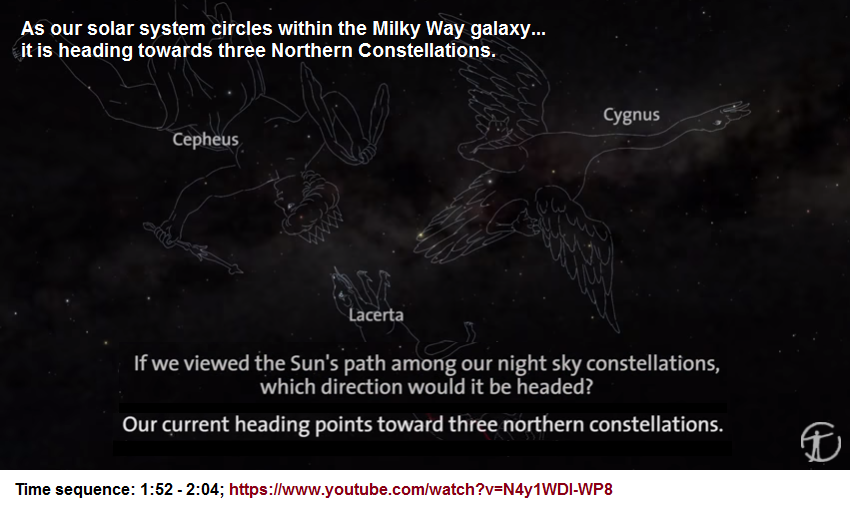

Let's take a look at some threes themes found in Astronomy, though you might be inclined to focus on the pattern-of-two organization called Binary stars, as I first was, until I came across three-patterned references associated with Binary orientations:

| |

|

|

How Does Our Solar System Move Around the Milky Way? |

|

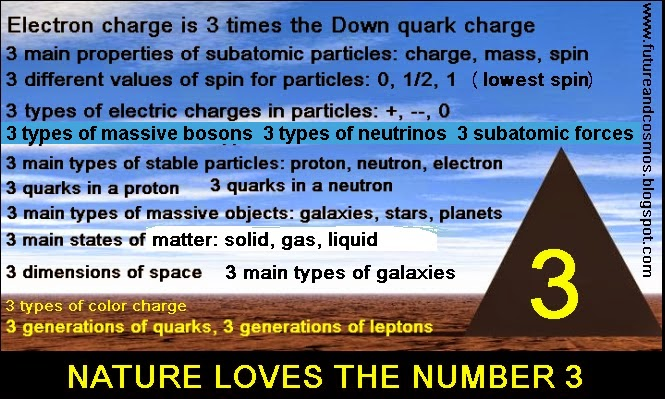

No less, an idea with a threes theme is inclined to be more receptive if the audience likewise is already predisposed towards accepting the presence of this particular theme as a recurring constant. And yet, how many concept creators and concept reviewers take the time to assess the recurring presence of "threes" not only in physics, but other subjects as well? And even if you are one who strives to point out another pattern as an argument, you don't further state it in the fashion of an absence of the three theme. In other words, it is of some interest not only to note the recurring presence of threes, but the absence there of... along with what other pattern(s) may be present instead. No less, an account of a threes theme in physics (as well as other subject areas), along with its absence and the presence of some other pattern, begs the question of why the overall count of recurring patterns is of a low value. In other words, why don't we have a hundred type of subatomic particles? Why is the Periodic table of elements such a low number? Why isn't Evolution evolving itself... such that the triplet code evolving to a four, five, six... etc., code quantity? Why the conservation? Or is the conservation due to a conserved piece of biological equipment called the human brain subjected to an inclemently deteriorating environment that it is forced into a state of conservation from which conserved ideas arise?

The problem with the following article and all those from the field of physics (and elsewhere), is that both the authors and researchers need to be skeptical because of the conserved nature of nature's patterns. What's this you say? A person interested in the threes phenomena bringing to the forefront a suspicion that the findings could be wrong... or at least the product of rationalization toeing the line of a biological requirement to express a practicality in concert with the incremental deterioration of environment for the sake of relative equilibrium? An equilibrium that gives the impression of a raft on an ocean where the main players are huddled together in the center and are therefore isolated from recognizing the rate and degree of deterioration that is readily seen by those on the outskirts of accepted rationality who are being dubbed a lunatic, rebel, maverick or iconoclast fringe?

One example of a rebel from the field of Biology as recorded in chapter 17 of the book Rebels Mavericks, and Heretics in Biology concerns the efforts of Carl Woese to establish a Three domain classification system in contrast to a two domain system that one can consider was established by a dichotomy oriented mindset. Similarly, with respect to physics, we should be looking to move beyond the particle/wave dichotomy. One effort along these lines is described here: Fragments of energy – not waves or particles – may be the fundamental building blocks of the universe. Whether or not one agrees with this particular perspective, the effort to develop a third item is a recurring cognitive constant. In other words, we often see a previously formulated dichotomy being altered to a trichotomy. Since this appears to be a recurring theme of cognitive behavior, we need to deliberately accept it as a valid form of inquiry as well as inquire into what is causing this "three" appearance. Is it a conserved survival measure in response to an incremental deterioration of the Sun's energy, Earth's rotation, and Moon's position?

Yep. Since we are finding both a limitation of patterns and a recurrence of a pattern-of-three in multiple subject areas, we need to consider the very real possibility that our biologically based... human... perspective may be dealing with yet another variation of rationalization brought to us by the incrementally deteriorating environment we are subjected to. The on-going incremental deterioration of the Moon's receding, the Earth's rotation slowing, and the burnout of the Sun, causes biological life forms to cope with the deteriorations by making adjustments involving tether lines of security seen in the usage of recurring patterns. While over the centuries adjustments are made to beliefs... that we can call rationalized reconfigurations, they are all adaptive responses to the deteriorating environment for which our biology is forced to create acceptable perspectives of compliance in order to make the best of an increasingly bad circumstance in terms of reduced resources. No doubt that in a more resource-lucrative environment opinions change, increasingly desperate situations will create conditions for increased conservation efforts in our perspectives. We must be wary about a total reliance on physics and mathematics, if not genetics and chemistry by which we steer our future course... that is, hopefully... off this planet, out of this solar system, and away from this galaxy.

And it's brought to you by the number three.

Jamie Seidel, News Corp Australia Network

May 30, 2014 1:27 PM

The rule of three has become something akin to a social law of gravity — as if the number is behind everything.

Forget pairs. They’re old pat. And 42? We still don’t know the question.

Comedians insist three is the best pattern to exploit perceptions and deliver punch-lines; three features prominently in titles, such as The Three Little Pigs, Three Musketeers, Goldilocks and the Three Bears; even the Romans believed three was the ultimate number: “Omne trium perfectum” was their mantra — everything that comes in threes is perfect.

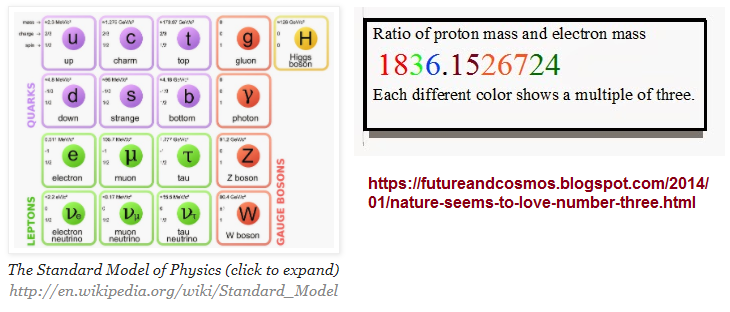

Now, it seems Mother Nature may also think in threes. (Nature Seems to Love the Number Three, by Mark Mahin, Friday, January 31, 2014) Especially at the very edge of physics — quantum mechanics.

A Soviet nuclear physicist first proposed the idea back in the 1970s — and was met with derision.

For 45 years number-crunchers around the world have been attempting to topple Vitaly Efimov’s idea and prove his equations wrong.

They’ve failed; and his “outlandish” theory is now on the point of being proven.

Most importantly, Efimov felt that sets of three particles could arrange themselves in an infinite, layered pattern. What form these layers take helps determine the makeup of matter itself.

Jump forward four decades, and technological advances now allow his groups of three quantum particles to be studied and manipulated.

The quantum condition — now known as Efimov’s state — is visible only under supremely cold conditions. Matter, when chilled to a few billionths of a degree above Absolute Zero, does strange things …

If you want the technical details, read Quanta Magazine’s article which examines the recent research papers.

But the behaviour of the particle trios is best summarised by physics professor Randy Hulet’s comment: “It’s like layers of an onion …. You see molecules at one layer. Peel the layer away, and you see that there’s a molecule there 22.7 times smaller. Every time you peel away a layer, you find another molecule.”

And guess which number appears to be proving his theory?

You guessed it: Three independent research groups in three different countries have now found Efimov’s predictions to be correct.

The upshot: We are now on the brink of a better understanding of how the universe works.

It’s all about a Russian-Doll-style progression of trios of particles, infinitely extending from the tiny quantum scale to that of the universe — and beyond.

It’s also an insight into how the insane world of quantum particles transforms into the predictable universe we inhabit.

“We are very excited about this result,” one researcher said. “In the complicated molecular world, there’s a new law.”

"The rule of three has become something akin to a social law of gravity as if the number is behind everything. Forget pairs. They're old pat. And 42? a Russian-Doll-style progression of trios of particles, infinitely extending from the tiny quantum scale to that of the universe and beyond. It's also an insight into how the insane world of quantum particles transforms into the predictable universe we inhabit. "We are very excited about this result," one researcher said. "In the complicated molecular world, there's a new law."

Richard Web

What is quantum physics? Put simply, it's the physics that explains how everything works: the best description we have of the nature of the particles that make up matter and the forces with which they interact.

Quantum physics underlies how atoms work, and so why chemistry and biology work as they do. You, me and the gatepost at some level at least, we're all dancing to the quantum tune. If you want to explain how electrons move through a computer chip, how photons of light get turned to electrical current in a solar panel or amplify themselves in a laser, or even just how the sun keeps burning, you'll need to use quantum physics.

The difficulty and, for physicists, the fun starts here. To begin with, there's no single quantum theory. There's quantum mechanics, the basic mathematical framework that underpins it all, which was first developed in the 1920s by Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrodinger and others. It characterises simple things such as how the position or momentum of a single particle or group of few particles changes over time.

But to understand how things work in the real world, quantum mechanics must be combined with other elements of physics principally, Albert Einstein's special theory of relativity, which explains what happens when things move very fast to create what are known as quantum field theories.

The billions upon billions of interactions in these crowded environments require the development of "effective field theories" that gloss over some of the gory details. The difficulty in constructing such theories is why many important questions in solid-state physics remain unresolved for instance why at low temperatures some materials are superconductors that allow current without electrical resistance, and why we can't get this trick to work at room temperature.

But beneath all these practical problems lies a huge quantum mystery. At a basic level, quantum physics predicts very strange things about how matter works that are completely at odds with how things seem to work in the real world. Quantum particles can behave like particles, located in a single place; or they can act like waves, distributed all over space or in several places at once. How they appear seems to depend on how we choose to measure them, and before we measure they seem to have no definite properties at all leading us to a fundamental conundrum about the nature of basic reality.

This fuzziness leads to apparent paradoxes such as Schrödinger's cat, in which thanks to an uncertain quantum process a cat is left dead and alive at the same time. But that's not all. Quantum particles also seem to be able to affect each other instantaneously even when they are far away from each other. This truly bamboozling phenomenon is known as entanglement, or, in a phrase coined by Einstein (a great critic of quantum theory), "spooky action at a distance". Such quantum powers are completely foreign to us, yet are the basis of emerging technologies such as ultra-secure quantum cryptography and ultra-powerful quantum computing.

But as to what it all means, no one knows. Some people think we must just accept that quantum physics explains the material world in terms we find impossible to square with our experience in the larger, "classical" world. Others think there must be some better, more intuitive theory out there that we've yet to discover.

In all this, there are several elephants in the room. For a start, there's a fourth fundamental force of nature that so far quantum theory has been unable to explain. Gravity remains the territory of Einstein's general theory of relativity, a firmly non-quantum theory that doesn't even involve particles. Intensive efforts over decades to bring gravity under the quantum umbrella and so explain all of fundamental physics within one "theory of everything" have come to nothing.

Meanwhile cosmological measurements indicate that over 95 per cent of the universe consists of dark matter and dark energy, stuffs for which we currently have no explanation within the standard model, and conundrums such as the extent of the role of quantum physics in the messy workings of life remain unexplained. The world is at some level quantum but whether quantum physics is the last word about the world remains an open question.

Date of Origination: 29 August 2020... 1:06 AM

Initial Posting: 29 August 2020... 2:18 AM

Updated Posting: 28th August 2021... 12:56 PM