A Study of the Threes Phenomena

Visitors as of April 14th, 2025

How the Third Event Signals the Emergence of a Streak

Kurt Carlson, Duke University

Suzanne B. Shu, Southern Methodist University.Abstract

It is well established that people perceive streaks where they do not exist. However, little is known about what constitutes a streak in the mind of an observer. This paper proposes that the third repeat event in a sequence is pivotal to the subjective belief that a streak is occurring. In five studies, we find direct and indirect evidence that perceived streakiness plateaus with the third repeat outcome in a sequence. The evidence to support this rule of three comes from various domains, including: observation of randomly determined probabilistic outcomes, investment decisions in response to performance histories, and basketball shooting percentages.

"When you win one, you stop a losing streak. When you win two, it's a trend.

Three in a row and it's a streak."

—sportswriter Anthony Flum, Boston Daily Free Press, 4/29/2005

"Nobody wants to lose two in a row, and definitely nobody wants to lose three in a row.

If you lose three in a row, there will start being a lot of questioning about our losing streak."

—Luol Deng, NBA basketball player

- A substantial body of research has established that people perceive streaks in random data (Gilovich, Vallone & Tversky, 1985, Allbright, 1993, Albert & Bennett, 2001).

- One of the most compelling results from the work on streaks is that people steadfastly maintain beliefs in streaks, even in situations where there is strong evidence to the contrary (Gilovich et al., 1985).

- The search for streaks in sports has led researchers to analyze data from the domains of professional golfers (Clark, 2005; Clark, 2003a; Clark, 2003b),

- sports gambling (Offerman & Sonnemans, 2004).

- and Long distance basketball shootouts (Koehler & Conley, 2003)....

...with the typical result that there is little evidence to support the existence of streaks. [The statistical existence of streaks has been identified in other domains; for example, Gilden & Wilson (1995) find evidence of streaky performance among putters and dart throwers.]

The primary concern of this paper is not the actual existence of streaks,

but the strong tendency of observers to perceive them to exist.

- Belief in streaks has also been studied in casino gambling (Croson & Sundali, 2005).

- and in investment decisions (Kahneman & Riepe, 1998, Hirshleifer, 2001).

For example, studies have shown that investors will buy assets that have recently increased in an attempt to chase a streak (Johnson, Tellis, & Macinnis, 2005), and that they overweight recent news and rumors when deciding to trade (DiFonzo & Borda, 1997).

Although much work has been done to compare subjective perceptions of streaks against their actual occurrence, little has been done to understand when observers believe a streak has emerged. In other words, at what point does a sequence of events begin to exhibit streakiness?

In this article, we propose and test the idea that the third repeat event in a sequence is pivotal to the belief a streak has emerged. Specifically, we propose that the third repeat event in a sequence signals the emergence of a streak. A consequence of this rule of three is that three sequential events (one original and two repeat events) should be perceived as streakier than a sequence of two events, and may even be as streaky as a sequence of four or more events. The rule of three draws support from the importance of the number three in human learning and cognition. Humans perceive the world in three dimensions and are capable of viewing only three basic colors. After three examples of a new word, people can generalize the definition of the word to new objects (Tenenbaum & Xu, 2000), a result consistent with work by Kareev (1995, 2000) on humans' tendency to pick up patterns in small samples. In marketing, three is the optimal number of advertising exposures during a purchase cycle to influence consumer behavior (Belch & Belch, 2001)...

While the paper did not go into a possible originating source for the recurrence of the "series-of-three" phenomena, it is of interest to point out an old expression which describes a "threes" reference that portrays an awareness of the "three" as a limitation:

While variations exist with slightly different wording, and though it has been attributed to Ben Franklin, it is said to have originated with the 16th century writer John Lyly. In his most famous work, Euphues – the Anatomy of Wit, he writes, "Fish and guests in three days are stale."

Source: The Truth About Ben Franklin’s Epigrams by Matt Blitz.

Both a cognitive series and limitation are expressed, and represents an area of research that has been overlooked by those who study literature, cognitive psychology, and philosophy. Take for example this short venture concerning Aesop's Fables which highlights a 1-2-3...Many representation.

I am not saying the foregoing expression is the primary influential source for all present day types of "3-part series", I however, am acknowledging the pattern's existence in former times when there was little to no organized sports... except for the occasional battlefield scenario which some think to be former exercises of inter-active sports. That is, instead of staying home and watching a sports game on television, the people of the past indulged in more life and death oriented behavior which evolved over time to our present day representations. Yet, this begs the question of whether that which we call sports is somehow linked to organized hunting and gathering of more primitive times. Nonetheless, if we broaden our search parameters in looking for earlier examples of the "threes series" phenomena one might cite the Pythagorean Theorem portrayed today as A22 = C2; even though the ancients used what are called Pythagorean triples since the letters of the defined English Alphabet did not exist.

And for those interested in a little more mathematical information, here is an excerpt from the Britannica:

Pythagorean triples:

The study of Pythagorean triples as well as the general theorem of Pythagoras leads to many unexpected byways in mathematics. A Pythagorean triple is formed by the measures of the sides of an integral right triangle—i.e., any set of three positive integers such that a2 + b2 = c2. If a, b, and c are relatively prime—i.e., if no two of them have a common factor–the set is a primitive Pythagorean triple.

A formula for generating all primitive Pythagorean triples is:

a = p2 - q2, b = 2pq, c = p2 + q2, in which p and q are relatively prime, p and q are neither both even nor both odd, and p > q. By choosing p and q appropriately, for example, primitive Pythagorean triples such as the following are obtained:

The only primitive triple that consists of consecutive integers is 3, 4, 5.

Certain characteristic properties are of interest:

- Either a or b is divisible by 3.

- Either a or b is divisible by 4.

- Either a or b or c is divisible by 5.

- The product of a, b, and c is divisible by 60.

- One of the quantities a, b, a + b, a - b is divisible by 7.

It is also true that if n is any integer, then 2n + 1, 2n2 + 2n, and 2n2 + 2n + 1 form a Pythagorean triple.

Certain properties of Pythagorean triples were known to the ancient Greeks—e.g., that the hypotenuse of a primitive triple is always an odd integer. It is now known that an odd integer R is the hypotenuse of such a triple if and only if every prime factor of R is of the form 4k + 1, where k is a positive integer.

Source: "number game." Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013.

Yet, we of today can only imagine how and why the idea of the Pythagorean theorem came to be generated since the use of triples in an ancient time and place may have had an enlarged significance to prop-up a users personal worth as well as provide a secret code which user name and password are present day expressions of the ancient "secret/sacred code" mentality remains very much alive, along with superstition, numerology and mental illness which become rationalized into acceptable contours of behavior by way of context and vocabulary such as we find in government and other "respected" institutions where wealth, property, power, sex and various types of intoxications exist.

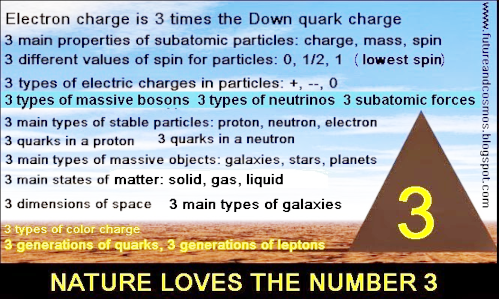

In the above excerpt about the "three" signaling what is sometimes called a "streak"... at least in sports, we need to realize that the word "streak" might well be viewed in other terms such as that when we describe the emergence of life after the establishment of the triple code in DNA. Indeed, if we call the emergence of life as a streak that continues today, we need also to acknowledge that DNA's triplet code may itself be a "streak" which originated after the "three" position of the Earth was established. Then again, the singular Earth may itself be termed a streak having occurred after 3 families of atomic particles were established and the 3 spatial dimensions. (Including the dimension of time makes the lineup a 3-to-1 ratio.)

On the other hand, with respect to DNA's triplet code, it is suggested it occurred after a doublet code which occurred after a single code. Such a consideration is not unfounded when we espy the 1-2-3 sequence occurring in other cognitive perceptions related to actual events such as the 1-point- 2-point- 3-point variations in basketball and the word-used variation known as (1) On/To Your Marks, (2) Get set, (3) Go! Not to mention the routine of some parents using a 1-2-3 counting method to direct one or more children to perform some activity that we can also sometimes see when a person is testing a Microphone while saying Testing, 1-2-3, or a group of musicians synchronizing a collaboration by someone saying "Uh one, Uh two, Uh three", etc...

We also have the 3 life domains and 3 Germ layers and the threes found in human anatomy. Each of them preceded another grouping of three and were followed by a set of three, even if there is no purposeful intention or acknowledgement by researchers in a given field of study. In fact, the overall series of recurring "threes" may be called a "streak".

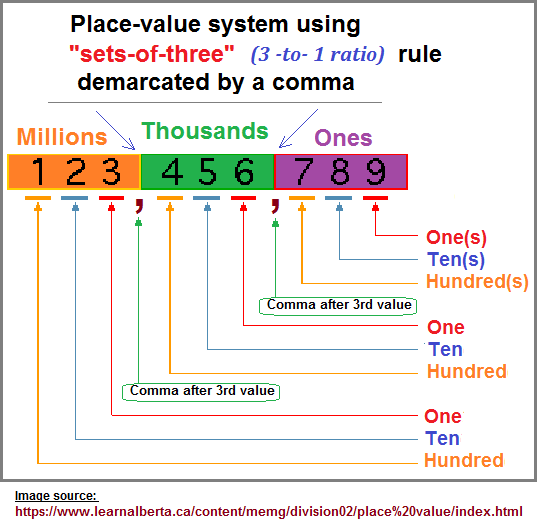

Clearly, a succession of "threes" has taken place to the extent some might describe as Nature Seems to Love the Number Three (By M. Mahin). Indeed, while not customarily referenced, events in Nature as outlined by Science portrays sequential events of development, unless you prefer to think that everything in Nature developed at the same time instead of over differing expanses of time. Science speaks of a history of development which frequently portrays patterns-of-three, at least from the human perspective. If another singular even takes place after a set-of-three, we may find ourselves using some method of selectively assigning the first three to a set or series marked off from another full or partial set of three. It is as if Nature is engaged in the usage of a value notation system, with respect to human perception. As such we might otherwise describe the succession of threes as a kind of compartmentalization but also a delineated limitation of human cognitive activity.

Every set-of-three apparently is preceded or followed by or attendant with another set which may contain 1, 2 or 3 members. In addition, there is an apparent means of isolating each set as a separate compartmentalization. Use of a comma, use of a space, use of a word such as "and", etc., may be used. In terms of describing a "space" we may use different words or expressions such as "empty", some sound, some gesture, some randomly occurring event, some taste, some feeling, etc... the point of demarcation is determined by context and the type of spoken/non-spoken language/symbology used.

However, let us not get too attached to the word "streak" which makes us overlook or even be dismissive of terms which can be viewed as being synonymous, such as series, sequel, pattern, repeat, repetition, etc...

Yet, in terms of using the word "series" with a conserved definition involving some notion of continuity that may be described as consecutive such as in the 3-4-5 sequence of the Pythagorean theorem, what if a series of human thinking takes place in different environments such as we find in history occurring with a particular discovery such as what is called the Mendelian 3 to 1 ratio code? While others had discovered what Mendel did, it is Mendel to whom the pattern is given his name as the discoverer. Isn't the discovery of a 3 to 1 ratio by other researchers a sequence involving human cognitive activity? Hence, sequences otherwise described as a series can well take place in different contexts. However, if our vision is limited to a single time and place or activity, then any larger human cognitive development of the species can go overlooked.

Use of the word "series" may well lead an observer to cite only those events occurring in a very narrow or strict domain of a specifically labeled behavior, and not consider attendant sequences. For example, I once observed a row of woman standing in front of a saddle-binder (at a commercial printing shop) with about 15 "pockets" in which stacks of pages for a magazine or book were place and followed a conveyor-belt like sequence which eventually ended up creating a magazine or book with sequential pages before the rough copy was subjected to trimming, stapling, stacking, strapping and then being boxed. As the woman worked side by side at a routine which cause enormous boredom, each of them in turn (on this one occasion of observation) would yawn in a sequential order from the 1st person to the last, though each appeared to be oblivious of the other performing the same behavior in a sequential fashion.

While attendant sequences may occur and be observed, if the researcher is not sensitively aware of this possibility, they may be dismissive of any other event (expressing a sequence or not), as an anomaly that need not be mentioned. In short, defining the parameters of a given research orientation within a narrow range of accountability, though the research may itself be one-of-a-kind and quite broad in this respect; limitations can lead to excluding relevant data from outside the rules which are alternatively described as axioms in mathematics and a brochure of rules accompanying board games.

H.O.B note: I have noticed that at different points in a given list of "threes" examples a person may become overwhelmed and react either positively or negatively. In other words, the limitation noticed by the authors as to when the idea of a "streak" may come to mind, also is evidenced when sequential lists are presented. In further words, the point at which a person may define an occurrence(s) as a 'streak' may be the same type of behavior concerning cognitive limitation seen when the person is supplied with a list. Not too many people would take the time to read a thousand examples of a given topic and few might even regard a list of 100 examples as being too many. Hence, all of this harkens back to the cognitive age of humanity in its early attempts to develop a counting system. The sequence of developmentally expressed cognitive limitation over time is thought to have occurred with primitive humans (in the realm of a developing number system). It expresses what might be perceived as an embedded cognitive pattern-of-three sequentially occurring like the (1s- 10s- 100s, set of three) value notation used in arithmetic, but is seen in other subjects with respect to the vernacular and symbology differentially employed.

- The concept of 1... everything else was many, much, more, heap or whatever word, symbol, or gesture was used at the time in the respective language equivalent way.

- The concept of 1 and 2... everything else was many...

- The concept of "many" is variously described today as plurality, infinity, the Universe., E Pluribus Unum (out of many, one)...

- Humanity has returned full circle to the "1" mentality by inventing ideas such a singular Omni-god, TOE (Theory of Everything), Universal Health care, Minimum (but no) Maximum wage, GUT (Grand Unified Theory), Singularity...

If we limit our research to an idea of strict sameness, we might want to say that the sequence: 1s- 10s- 100s (comma) is not the same as 1,000s- 10,000s- 100,000s (comma)..., even though by convention many of us see the under- and over-lying patterns. Sameness can inadvertently imply mirror-images or copy-cat impressions. In both cases, the limit is a set-of-three followed by a comma, though a 1 or 2 may precede a set. The "three" need not come first, just as a second set-of-three need not contain all the members. It could well contain one or two, thus distracting an observer from recognizing that another set-of- three has been abbreviated or cut short for some reason. The comma can thus be described as a point of demarcation between sets of three, yet if we place the sequence: [1s- 10s- 100s (comma) 1,000s], we might call it a sequence of four if we did not have any experience with larger number values or did not use a comma. It is by comparison that we apparently come to distinguish the larger conceptual value of the overall series. In other words, the first set of three [1s- 10s- 100s] is difficult to ascertain without attendant attributes such as the use of a demarcating comma and larger number values representing distinctions. This same cognitive patterning is seen in the sequencing values of RNA and DNA when I cite that three are the same and 1 is different:

- RNA: Adenosine- Cytosine- Guanine, Uracil

- DNA: Adenosine- Cytosine- Guanine, Thymine

- Proteins: Secondary-Tertiary-Quaternary structures are ribbon-shaped; Primary structure is not ribbon-shaped.

- Mendelian genetics describes 3-to-1 ratios

- There are 3 face cards to 1 Ace in a deck of cards.

- The 3 bears and Goldilocks.

- The 3 fiddlers and Old King Cole.

- The wolf and the 3 little pigs.

- etc...

See: Aesop's Fables for a breakdown of cognitive patterning using a "1-2-Many" profile.

Origination: Sunday, April 13th, 2025... 8:09 AM

Initial Posting: Monday, April 14th, 2025... 11:22 AM

Updated Posting: Monday, April 21st, 2025... 11:59 AM